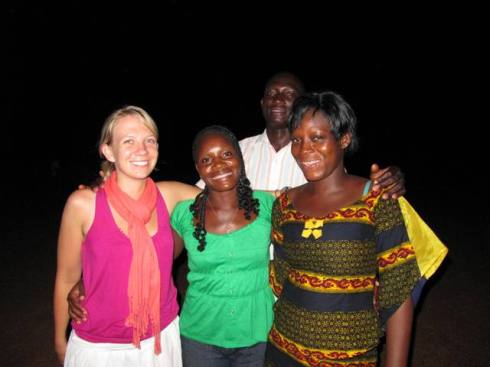

Two weeks ago, I got onto a plane in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, destined for Toronto, Canada. When I crossed the airplane’s threshold, I stepped into another world; a world that most of my Burkinabè friends will never have the chance to see. To cross that threshold into the “developed” world, you must be a member of a fairly exclusive club, which admits mostly westerners and the most highly educated, wealthy citizens of southern and eastern nations. In this other world, life is very different.

Upon returning to Canada, I found a job in one week, and started working the next day. My friend Tinda in Burkina Faso has been looking unsuccessfully for work for 20 years, and has still managed to raise a family and take in several nieces and nephews who have nowhere else to go.

I start my university classes tomorrow. My Burkinabè sister Alizeta, who is the same age as I am (25) has been struggling for years to be able to complete her studies up to grade nine – working in the fields to feed the family had to take precedence.

Upon my arrival to Calgary, I had several affordable housing options – each with my own room. Apollinaire, Wendenso, Adambila, Cyril and Alidou, all young students aged 8 to 14, share one mattressless room without complaint, just to have access to an elementary education.

I do not wish to belittle the lives of my friends; on the contrary, I want to highlight the incredible strength and potential of many of the wonderful people I met during my time in Burkina Faso. After spending time there, I don’t believe that it is simply the poor people of Burkina who need to change in order for their country to rise above the poverty line. They work incredibly hard every day just to put food on the table, and given a good and fair opportunity, they would happily haul themselves out of poverty. Unfortunately, most of the time, those kinds of opportunities just aren’t within reach.

It is the countries with strong economies – those who have the ability to impose (and to remove) powerful trade barriers and who decide when, where and how much aid is given – who have the biggest influence on whether or not Burkina Faso, and many other countries facing even more staggering poverty will make it out alive.

If rich nations are going to use their power for good, it is their citizens who must communicate to their governments that the eradication of poverty is a priority. As a Canadian, I have a say in my governments’ actions. With that power comes responsibility – the responsibility to use the freedom I was given (simply for being born in Canada) to help others access the freedoms and opportunities that I have. Freedom from hunger, from preventable and curable diseases, from abject poverty. The opportunity to study, to work and to choose the kind of life I want to live.

When I got onto the plane in Ouagadougou, destined for Toronto, I stepped into another world. I did not earn my place in this world; I was born into it. And now, I’ll use that place to play my part in the change that sees the end of extreme poverty.

Thanks so much for taking time out of your busy lives to read about my adventures, about life in Boulsa and Dargo, and about the friends I met and the lessons I learned. Your support inspired me to keep writing about it!

Although I am back in Canada, I am still going to blog every now and then – I’m committed to learning more about how to make the world a better place for all the people who live here. I hope you’ll be there to listen!

Until next time,

– Chelsea

Resources, inspirations and ways to get involved

If you’re interested in learning more, or getting involved in international development, you are in luck! There are many ways to do so:

1. You can take out some of these exceptional books at your local library:

- The Shadow of the Sun by journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski. This book took my breath away. It is an incredible collection of short stories about life post-independence in several African nations.

- Stephen Lewis’ Race Against Time, a collection of lectures Mr. Lewis, the United Nations Special Envoy to HIV/AIDS in Africa, gave as part of the CBC Massey Lectures. A must read (or listen).

- Chinua Achebe’s acclaimed classic Things Fall Apart is the most widely read African-written novel in the world, having sold several million copies since being published in 1958.

- Ian Smillie’s Freedom From Want: The Remarkable Success Story of BRAC, the Global Grassroots Organization That’s Winning the Fight Against Poverty offers important insight into what good development can look like.

2. You can write to your Member of Parliament to ask “So, what is Canada doing in the fight against extreme poverty?” Don’t know who your MP is? Click here to find out!

3. You can learn about the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals. Did you know that the UN committed to reaching several goals related to global poverty by the year 2015? Some of the goals include:

- Reduce extreme poverty by one half

- Reduce under-five mortality by two-thirds

- Achieve Universal Primary Education

- And many more…

4. You can get involved with a non-government organization in your community. There are many groups who are doing really good work locally and internationally who would love to have you as a volunteer (beware – there are some who are doing not-so-good work too… one tip is to look for organizations that are focused on continuously learning from past experiences, good and bad).

Thanks again.